La Sylphide, I recently discovered, is the ballet that set in motion the stereotypical notion of the ballerina: pointe shoes, tutu, fairy dust. It kicked off the fruitful Romantic Period in ballet and enabled such repertory stalwarts as Giselle and Swan Lake. With the invention of the pointe shoe, which was first used to great effect by Marie Taglioni at the premiere of La Sylphide in 1832, ballet blossomed into a form of allegorical poetry. Despite the strict, hierarchical codification inherent in ballet from its basis in the royal courts, the pointe shoe managed to transform female dancers into

Marie Taglioni’s Sylphide was legendary, and she became a huge star in Paris. But the original incarnation of the ballet—with choreography by her father and music by Jean-Madeleine Shneitzhoeffer—has been mostly lost. It is La Sylphide’s second iteration (like many a Bob Dylan cover) which is considered the definitive version, the one that is still performed today. This 1836 version by August Bournonville is the one the NYCB added to its rep this season, and it has survived basically intact for over 179 years!

Bournonville’s version uses the same Adolphe Nourrit libretto as Fillipo Taglioni’s, but the score is by Danish composer Herman Severin Løvenskjold. Bournonville made the male lead, James, far more important in his version, and danced the role himself at the premiere (opposite to his 16 year old protégé Lucile Grahn as the Sylph). His Sylphide reflects the mores of the Danish Golden Age (1800-1850). He was an exact contemporary and friend of Hans Christian Andersen, and he was close with philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen. It was a period during which people showed a renewed interest in Norse mythology, Danish nationalism, and old fashioned fairy tales.

This was not just the case in Denmark. In the 19th Century Romanticism held sway in music and literature. The end of the French Revolution incited a nationalist fervor which spread across Europe. The neo-classical, rational Age of Enlightenment had led to the grimy and dispassionate Industrial Revolution, and people all over were feeling a little bit like cogs in a wheel—mindless slaves to the very machines that were supposed to be so helpful to society. The art of the Romantic Era brought with it a focus on individual feeling; it wallowed in emotional extremes. Romanticism was about sensation over logic—Beethoven over Bach. There was a renewed interest in the occult, ghosts, dreams, eroticism and psychology. People longed for magic, and they mostly found it in the sublime, sometimes horrific power of nature. I think of Ahab’s white whale, Heathcliff on the moors, tiny boats tossed upon the stormy canvases of Turner and Géricault.

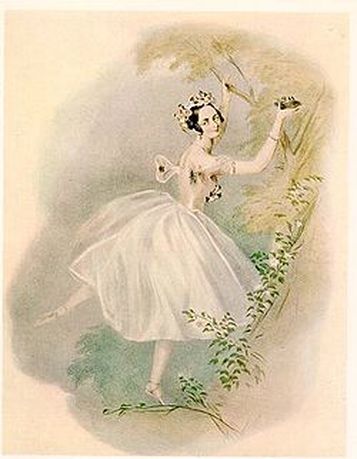

Enter the sylph—a woodland sprite, light on body but long on feminine wiles. She appears to bridegrooms in their dreams to lure them from their betrothed on their wedding days. She is an escape from bourgeois duty and quotidian ennui. She is pure id, nearly a yahoo, whimsically flitting from one stimulus to another—a bird! a butterfly! a shiny wedding ring! One can see why she was the heroine of the times. In the context of the Sylphide story her revealing, featherweight tutu and pointe shoes put her in stark contrast to James’s earthbound fiancée Effie in her thick kilt and clogs. The sylph was desire and liberty incarnate. James’s real wedding loomed like a yoke around his neck.

Someone asked me why La Sylphide is set in Scotland despite its French and Danish pedigrees. I can only speculate that it is because the Scottish highlands were like catnip to artists in the Romantic Era. Donizetti’s opera Lucia di Lammermoor (based on Sir Walter Scott’s novel The Bride of Lammermoor) premiered in 1835, in between Taglioni’s and Bournonville’s Sylphides. The poetry of Robert Burns was incredibly popular at the time, and Sir Walter Scott was alleged to be Marie Taglioni’s favorite author. The term Romanticism is perhaps linked to the French word for novel: roman.

La Sylphide is the prototypical ballet blanc—or a ballet with a first act set in the real world and a second act set in some mystical, often outdoorsy, plane. Giselle goes from the village square to a haunted graveyard; the first act court scenes of Swan Lake, La Bayadere, and The Sleeping Beauty are juxtaposed by second acts in a magic pond, the kingdom of the shades, and a fairy’s vision of an alternate reality, respectively. Even the late 19th Century Nutcracker goes from a living room party to a magical white snow scene and finally a fantastical kingdom of sweets. These ballets are utterly formulaic. They all present a milieu which is stifling to a hero figure, and then they provide an aesthetic escape and a non-human, yet erotic, muse for him.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed