Am I Doing This Right?

Recently, after a friend of mine came to the ballet, he told me he thought it must be nice to have a job where there’s such a clear right and wrong. There are the steps you have to do, he said, and there’s a right way to do them. It seemed like such a strange thing to say after seeing the ballet. He’s not wrong though. But he’s not right either.

It’s true, there is set choreography in almost every piece we do at New York City Ballet (it is a rare ballet in our rep that has any moments of improvisation), and it’s possible to do the wrong movement, to incorrectly execute a step or sequence of steps, and to dance at the wrong time, but that doesn’t mean there’s only one way to do it right. There are disputes regularly among dancers and ballet masters about what the choreography really is. Different people remember different steps. In part, these discrepancies exist because many of the ballets we dance have been adjusted over the years.

Beyond arguments about what the right steps are, there is also the question of how to interpret a role. If you do the choreography correctly, it does not guarantee you are giving the piece the right feel or that it will be compelling. There’s more to being a good dancer than doing the right steps at

I enjoy figuring out how I want to dance a particular part, and when I’m learning something new I like to watch tapes of old performances for ideas. The many different dancers Balanchine cast in his ballets performed with different intentions, and sometimes he gave them completely different steps. Each interpretation is valid, each step “correct,” but all are different.

The dancers and ballet masters in our company are also divided about watching old tapes. Some think it’s a good way to get inspiration, while others think a dancer should find their own way and not be influenced by previous performances. I watch tapes to get a feel for the ballet as a whole and to see what I think will and won’t work for me and for the piece. I never try to dance a role like anyone else, but sometimes I hold my arms the way someone else did, or I try to present myself in a certain way because I like how it looked. Seeing how other people have danced a part helps me to think about, and begin to decide, what my personal “right” way to do a ballet might be.

Duo Concertant was choreographed by Balanchine in 1972 for the Stravinsky Festival. I’ve watched this ballet many times over the years—it’s a staple in the company’s repertoire—but it was never a ballet I aspired to dance. Or rather, it’s not a part I’ve ever seen myself being particularly suited to dance. With all the fast footwork, and the typically petite women who perform it, I assumed my height and gangly limbs would rule me out. But I was wrong. I've been rehearsing Duo for the last few weeks and was just cast to perform it with Sterling Hyltin in the second week of our spring season.

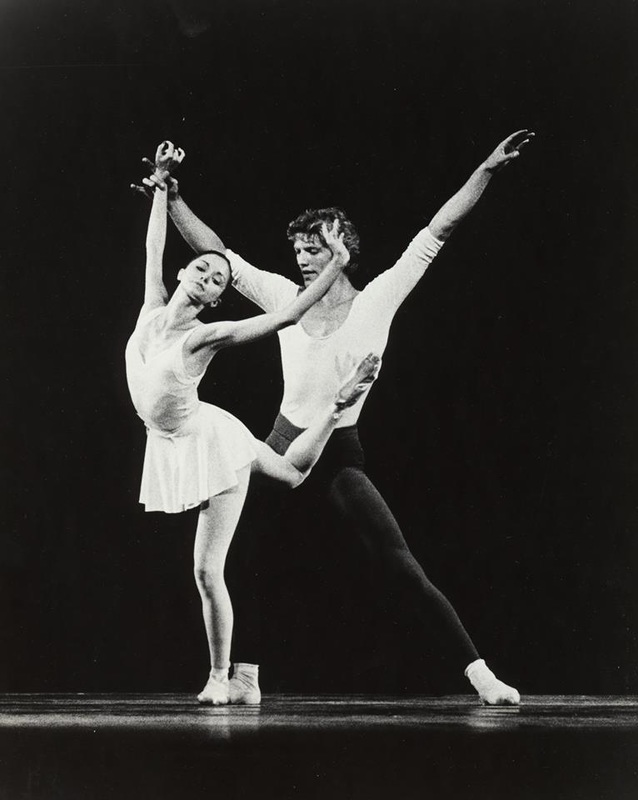

After learning the choreography from ballet mistress Glenn Keenan, I spent an hour last week watching tapes of past performances: Peter Martins and Kay Mazzo who originated the roles, Peter and Suzanne Farrell, Sean Lavery and Suzanne, and Robbie Fairchild and Sterling. From the tapes I picked up partnering tricks, subtleties in the choreography I had missed, inspiration for certain steps, and a few insecurities.

The steps were more or less the same in each tape, but the three men’s attack, and their presences in the ballet were quite distinct from one another. They all brought something different to the role. Sean is unbelievably light and agile despite his height; Robbie makes so much out of what I had previously considered fairly straightforward steps by filling out simple movements so that they almost explode into something more; and watching Peter’s casual elegance and self-assured dancing, you can tell the role was made for him.

I’m not capable of doing Duo like any of these three, which is… disheartening, because they’re all so good! After watching these different performances, I had to remind myself that beyond holding my head differently here, or changing the direction of my gaze there, I should not try to get any more from Robbie, Sean, or Peter. Their vastly differing performances, more than anything, have driven home the importance of humanity and individuality in this role. The dancers onstage in Duo are two real people with their own special way of interacting with each other and with the music.

It’s a quirky ballet, alternately charming and haunting. The setting is casual and intimate; the two musicians, a violinist and a pianist, are onstage with the dancers. In the first movement the two dancers stand behind the piano and listen. These opening moments seem to encourage the audience (and the dancers) to give equal attention to the music, and to show the impulse for the steps that follow. Stravinsky’s music is rich and complex, and with the dancers always returning to the musicians to listen it shifts the focus of the piece from the dance to the music. The score isn’t dictating the dance so much as it is allowing for the dance to happen. The choreography is casual, but ebullient. In the video I watched of Peter and Kay it looked like there couldn't possibly be anything else they would do to the music, so suited for the steps was their movement and demeanor.

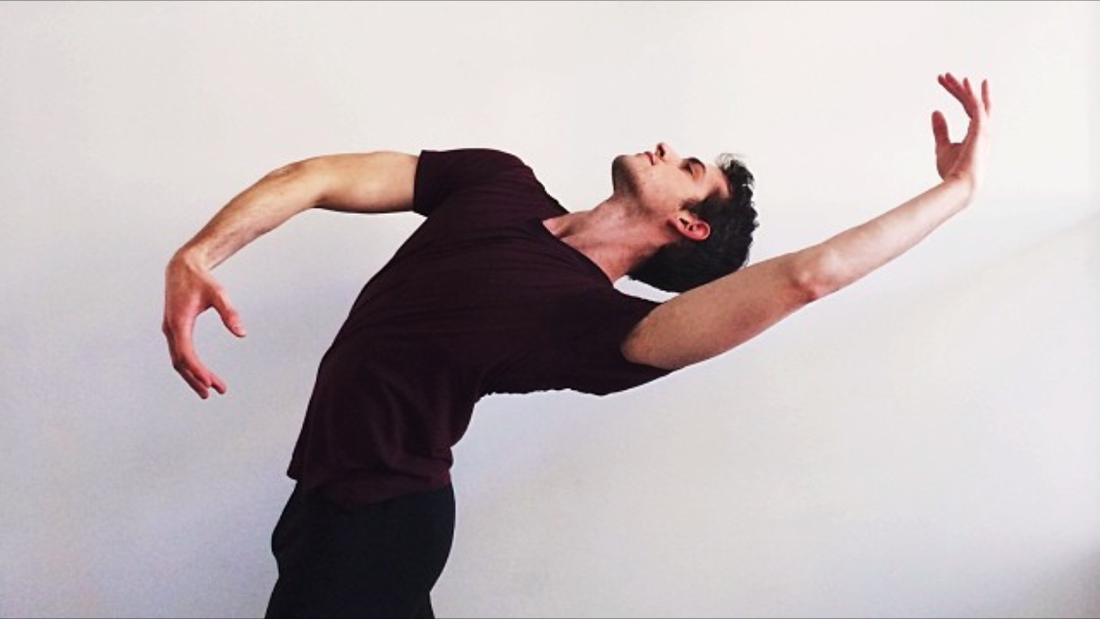

Sterling and I are beginning to develop our own rapport, both with each other and with the piece. Since she's been doing Duo for quite a few seasons now, I want to try to fit in with her idea of the ballet while still finding my own way. We’ve had few rehearsals together (I first learned the part with Ashley Bouder), and we’re figuring out how our partnership will work best in the piece. How do we play up our size differences without looking goofy? How do I bring my own humanity and style to the piece in a way that compliments Sterling and doesn’t sacrifice the integrity of the choreography? For me, a lot of this is figuring out how to think about steps and gestures in a way that makes them feel natural to me, like something I would do. This doesn't mean that all of the steps have to feel good on my body necessarily; it's more about finding believable intentions for myself.

After the amount of rehearsal I’ve had, I’m expecting that when I get out onstage I’ll be able to correctly execute the right steps at the right times, as my friend suggested, but I’m hoping for more. I hope to be able to carve my own way in this ballet, and this might take a few shows. Or a few seasons. Or a few years. I think I’m starting to find myself in the choreography, but this one will take time before it begins to start feeling right.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed