Photo by Paul Kolnik

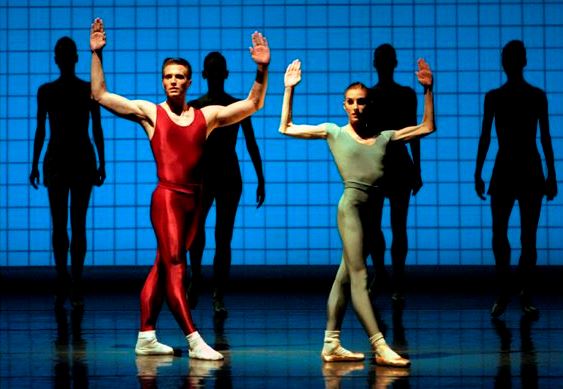

Photo by Paul Kolnik The first movement of this tripartite ballet is set to Rubric from Philip Glass’s 1981 album Glassworks. It is an energetic amalgamation of cascading horns and synthesizers held together by a steady driving beat, a complex cacophony that Robbins said, “felt like spaghetti” to him. The curtain rises on an empty stage adorned with a graph-paper grid backdrop. Robbins came up with the idea

In front of this gridded framework, dancers in colorful practice clothing flood the stage as the music’s chorus commences. They walk erratically, and audience members are often surprised to know that only the first few dancers have set counts and paths; the rest of the corps de ballet may enter, exit, and navigate at random. As long as they dance the walking “steps” in unison, they can perambulate on a whim. With a shift in the music, a man and a woman in shiny yellow unitards jump through the thronging crowd. This soloist couple remains onstage as the masses filter away and they dance an angular, acrobatic pas de deux to the music’s first verse. This pattern repeats thrice, with two new sets of shiny pastel soloists—in pink and then green—appearing and joining the original couple for a series of geometric yet balletic interludes.

The music sounds futuristic, and when the first couple jumps onstage in shiny gold spandex I always think of Constantin Brancusi’s aerodynamic “Bird in Space” sculptures from the 1920’s. In the rehearsal tapes Robbins promulgates this sci-fi bent and tells the dancers to imagine laser beams coming out of their fingertips every time they perform a thematic lunge step. There is also an undeniable urban vibe to the proceedings of the first movement—it almost appears as if the fresco of astrological constellations on the ceiling of Grand Central Station has come to life to soar over and through the traffic of the rush hour commuters in the great hall below. Robbins was no stranger to urban street scenes--Fancy Free, West Side Story, and N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz all attest to his preoccupation with conveying the vibrancy of city life through dance.

The crystalline movements of the Rubric soloists have a tremendous influence on the swirling pedestrian masses of the corps de ballet. With every new visit from the soloists the choreography for the walking corps becomes more intricate—with added turns, sharp arm movements, and small staggering steps—until finally all of the soloists enter and lead the corps in a series of crisp lunges in undulating patterns across the stage (the dancers call this section “waves,” aptly). Once the ebb and flow of the wave pattern has been established and performed by the entire corps, the soloists stop as the corps dancers continue to mimic their lunges. But as soon as the soloists cease to perform the steps with the group, the structure falls apart and the corps lunges in erratic patterns—again, unspecified by Robbins—around the stage. The soloists walk statuesquely through them for a moment and then fly offstage as the crowd resorts back to its original walk. Moments later, the music abruptly comes to a halt and the corps dancers freeze mid-stride, almost as if they have been paused by remote-control. Thus ends the first movement of the ballet.

In the rehearsal tapes Robbins tells the corps that their turns, pliés, and staggering steps must appear to happen out of the blue and not of their own volition. He insists that they cannot broadcast any physical preparation for their sudden moves or shift their weight to accommodate their quick stops—a difficult task for classically trained ballet dancers who work their whole lives towards disguising the effort behind their movements. Robbins had delved into the idea of possession in earlier works—notably in The Dybbuk from 1974—but in Glass the masses seem not so much possessed as guided or enlightened, civilized perhaps. To my mind, the soloists, be they members of an alien race, celestial deities, artistic muses, forces of civilization, or abstract mathematic principles made flesh—serve to organize the chaos. They wholly embody Milton’s poetic phrase in Paradise Lost: “order from disorder sprung.”

Conversely, Deborah Jowitt remarks in an early review of the piece in the Village Voice that to her, the mob in Rubric seems to give birth to the soloists. I rather like this idea too, as if the soloists are the embodiment of the common man’s own great notions. It is also interesting to consider—along the lines of scientist Richard Dawkins in his book The God Delusion (2006)—that humans have created and destroyed myriad Gods throughout the ages, and perhaps Robbins was depicting that trend in this ballet. It is after all a ballet that is in deep conversation with the ancient world (more on that later). My boyfriend thinks that the Rubric movement is simply a ballet version of the 1976 film Logan’s Run; and he laments that Robbins never got around to doing a Blade Runner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed